From: R

Saudi Arabia turns against political Islam

The crown prince tries to reform Wahhabism and isolate the Muslim Brotherhood

HOW TO OVERTURN God's law? Or, rather, how to change what you had previously said was God's law? This is the question facing Muhammad bin Salman as he loosens social restrictions. His conclusion? Blame it all on Iran. The crown prince says his country took a wrong turn in 1979. That was the year when Shia Islamists overthrew the Shah of Iran, Sunni extremists opposed to the Saudi monarchy stormed the Grand Mosque in Mecca and the Soviet army marched into Afghanistan.

Before that, so the story goes, Saudis could enjoy cinemas and concerts. Even in the time of Abdel Aziz Al Saud, the founder of the modern Saudi state, women worked in the fields and rode camels alone. But after 1979 Saudi kings, who call themselves custodians of the two holy mosques, resolved to outdo their foes, both Shia and Sunni, in Islamic piety.

The more relaxed social rules now being introduced are thus no heresy, says the crown prince; they are simply a return to a pre-existing normality. "Islam is moderate in its ways. It is unfortunate that extremism has hijacked this religion," says Sheikh Mohammad Alissa, head of the Muslim World League, a body that has long spread ultra-puritanical ideology. It is a sign of the new times that, these days, it is busy making ecumenical contacts with Christians, Jews and others.

For Stephane Lacroix of the Sciences-Po university in Paris, the crown prince is building a myth: "Saudi Arabia's religious authorities were extreme even before Ayatollah Khomeini ruled over Iran." The difference, he says, is that after 1979 they were given free rein to impose their rules in corners of the kingdom from which they had previously been kept out, such as wealthy neighbourhoods of Riyadh. With the emergence of global jihad, Saudi rulers have struggled to avoid association with extremist groups such as al-Qaeda, the Taliban and Islamic State (IS), whose religious practices and doctrines resemble those of Saudi clerics except in when and where to resort to political violence.

How can Saudi authorities distance Wahhabism from jihadism? One argument is semantic. They deny that there is any such thing as Wahhabism; what they practice, they say, is plain Islam as it existed among the salaf, the generation of the Prophet and his companions (thus they accept "salafism"). A second defence is doctrinal. Real salafism is quiet and non-political, they say. "It dictates that we should obey and hear the ruler," says Sheikh Mohammad. A third contention is that, if salafists have become rebellious, that is because they have been infected by the ideas of the Muslim Brotherhood. Founded in Egypt in 1928 during the agitation against British rule, the Brotherhood has inspired political Islam across the Arab world under different names, and with various degrees of militancy—from Ennahdha, the "Muslim democrats" of Tunisia, to Hamas, the armed Palestinian movement that rules Gaza.

Brothers are often less puritanical in Islamic practices than salafists but, because they permit rebellion against impious rulers, they are regarded as more subversive. Still, early on the Brothers enjoyed good relations with Gulf rulers, who thought them useful against nationalists and leftists. But after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, when part of the Brotherhood supported Saddam Hussein, the Islamists were regarded with greater suspicion. In many Arab countries the Brothers established themselves by providing social services for the poor. In the rich Gulf, the Brotherhood developed a form of "rentier Islamism" in which opposition was based on religious issues, says Courtney Freer of the London School of Economics. "Islamists have not tended to focus on economic policy," she argues. "Theirs is a moralising agenda. For them, governments have to prove that they are guardians of the morality of the nation."

Muhammad bin Zayed of Abu Dhabi, the main power in the United Arab Emirates, regards the Brothers as a menace. The UAE has arrested scores of their activists. Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad of Qatar, by contrast, has been a principal sponsor of the Brotherhood (see next article). Under Muhammad bin Salman, the hitherto ambiguous Saudis now side with the Emiratis. He speaks of a "triangle of evil" encompassing Iran, IS and the Muslim Brotherhood. As such he seems to be drawing a dividing line between Arab states (and tame salafists) on one side, and all forms of Islamism on the other—be they non-violent Brothers or jihadists. "It is a crazy analysis about the threat of a pan-Islamic empire," says Jamal Khashoggi, a former editor of al-Watan, a Saudi-owned newspaper, who now works as a columnist in exile in America. "He treats IS and the Brotherhood as the same thing—the only difference being that IS tried to create the caliphate immediately by violence while the Brotherhood wants to create the caliphate slowly, through democracy."

Although the Brotherhood never seemed very strong in the Gulf, its election victory in Egypt in 2012 unnerved Gulf rulers. Saudi Arabia and the UAE enthusiastically supported the coup that overthrew President Muhammad Morsi of the Brotherhood, not least because he was moving closer to Iran. For Mr Khashoggi, the campaign against the Brothers is an attempt to extinguish the last embers of the Arab spring: "Democracy and political Islam go together."

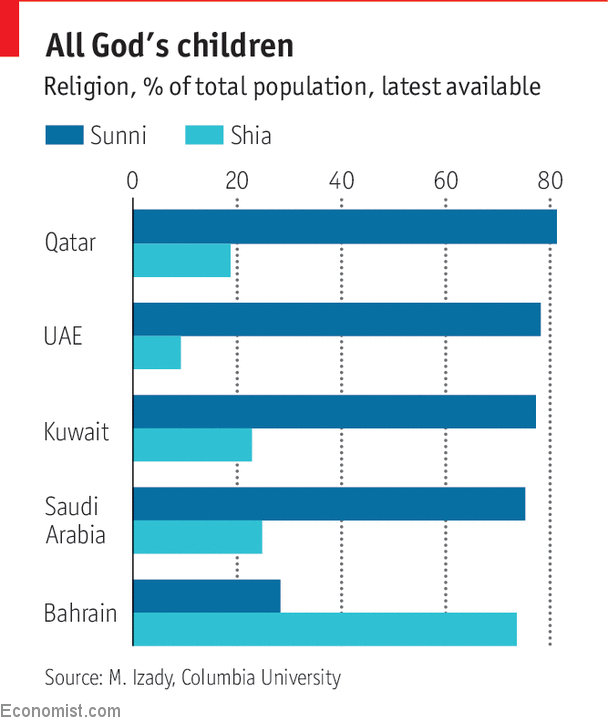

The Saudi push for "moderate Islam" may have one paradoxical boon. Many Shias hope it will quieten the worst anti-Shia utterances of Wahhabi clerics. Shias form substantial minorities across the Gulf (see chart). Many of them live over the richest oilfields. So episodes of Shia rebelliousness carry not just the fear of separatism, or of Iranian interference, but of economic disaster, too.

To varying degrees, Shias feel discriminated against across the GCC. They are often the downtrodden "other", regarded as a fifth column for Iran if not as outright infidels. During the Arab spring in 2011, many Shias took to the streets to demand greater freedom. The worst unrest took place in Bahrain, where Sunni rulers crushed protests by the majority-Shia population.

In Saudi Arabia, protests broke out in the Qatif region. Repression set off a spiral of bloodshed, and armed clashes in Awamiyah, home to a radical preacher, Nimr al-Nimr, who was executed in 2016. The unrest has been quelled and the town centre bulldozed. Prince Muhammad now seeks to distinguish between Shias and Iran. But resentment runs deep. "The people who took up arms were criminal," says one local Shia activist, "but the Saudi government is even more criminal."

No comments:

Post a Comment